Last week, my Memoir II writers offered up some of the many ways other people try to shut down our work:

It’s disrespectful to joke about such a serious subject.

What will your mother think?

Sounds like maybe you’re still too close to the material. Maybe you should wait a few years.

You’re not a real writer if you don’t put words down every day.

Yes, but what about your mother?

What struck me about all this advice is that, while often well-meaning, it does not indicate possible harm, so you can avoid it. It presumes that writing is harm.

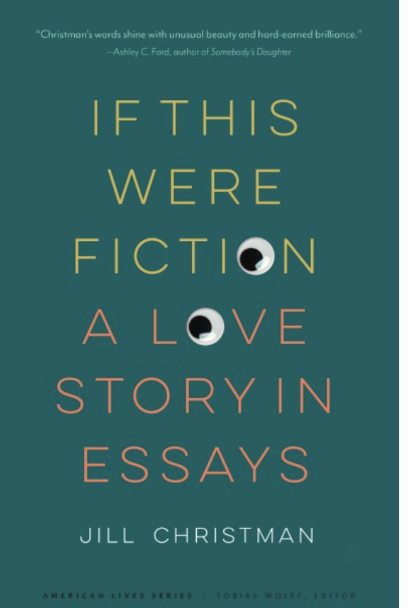

Luckily, author Jill Christman, who just published a book of love stories, was in the room, too.

“Having people tell you that you can’t tell your story, even if it intersects with theirs, that’s not a loving thing to do,” Christman said. “It’s not a loving thing for them to do to us.”

Or to ourselves.

In her book If This Were Fiction: A Love Story In Essays, Christman recoils from nothing. She writes about all the terrible things, which I won’t list, only to say that she doesn’t flinch from the ways that life beats you up. But she doesn’t leave it there.

Each essay finds a new answer to the question, when you know how much suffering the world can inflict, how do you love anyway?

An answer: You laugh. You love your people. And you write your stories.

As life philosophies go, we could do worse.

It’s often said, writing is cathartic. The author Brian Doyle said “writing is a time machine, writing resurrects, writing gives death the finger. And so amen.” Novelist Walter Mosley says writing is revelation.

What would happen if we thought of writing as love?

I’m not saying, write with love, or from a place of love. Because I believe it’s more than OK to write with or from fury, humor, sadness, delight, curiosity, spite. Rather, what if we thought of the practice itself as love, the way, sometimes, making someone a peanut butter sandwich is love, regardless of how you feel about that person, or about peanut butter, in the moment.

Would it make our stories better? Maybe. Maybe not. But it could turn down the volume on the censors who are always nagging at us. It could perhaps quiet the unreasonable expectations we heap on ourselves.

Such a shift in thinking could, I believe, free us, to let our stories take us to the surprising, unexpected places they’ve always wanted to go. Which is why we were moved to write them in the first place.

“Writing automatically, by its practice, feels like a safe place to me no matter where I’m going,” Christman said. “If I’m being honest, writing really is my safe space.”

Kelly Caldwell, Dean of Faculty