A thing writing teachers (including me) love to say is “Write from the scar, not the wound.”

A thing writing teachers (including me) love to say is “Write from the scar, not the wound.”

It’s good advice – for more on why, listen to Joselin Linder talk about it on Gotham’s Inside Writing) – but as we move into month 111 of living through three global crises, I’ve been thinking about the value of writing from the wound.

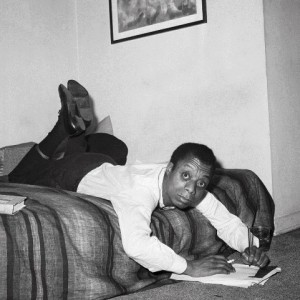

Consider the work of James Baldwin. In essays and fiction, Baldwin chronicled the pain of racial injustice, the turmoil of desegregation, and the voices, violence, and victories of the Civil Rights movement. Sometimes he wrote about crisis as it was still unfolding; sometimes, he wrote about it a decade or more later, with hindsight.

In both cases, his work was always urgent, moving, historic.

The risk writers take in writing from the wound is that the roiling emotions of the moment—fear, anguish, rage – can overtake you, reducing your work to a screed, not a story. To do it well, as Baldwin did, the key is to catalog your feelings, yes, but also the details creating them.

This is what Baldwin did in his essay “The Hard Kind of Courage.” He wrote it in 1958, mere months after visiting Charlotte, North Carolina, as it de-segregated its public schools in the wake of Brown vs. the Board of Education. He spent time with a teenage boy named Gus, the first and only Black student in a previously all-white high school. He spoke at length with Gus’ mother, about why she sent Gus to that school, and her fears and her hopes. He interviewed the white principal of Gus’ school, a man navigating an ocean he never imagined could even exist.

Baldwin details Gus’ laser-focus on his homework, his mom gazing out her window, the principal leading Gus through a mob, pretending not to hear the slurs shouted at his back. Through those details, the reader feels all of it – the rage, the fear, the uncertainty at what might lie ahead, hallmarks of those early days of de-segregation.

But the essay is more than mere observations, beautifully wrought. Baldwin also writes:

“For segregation has worked brilliantly in the South, and in fact in the nation, to this extent: It has allowed white people, with scarcely any pangs of conscience whatever, to create in every generation, only the Negro they wished to see. As the walls come down, they will be forced to take another, harder look… and will be forced into a wonder concerning them, which cannot fail to be agonizing. It is not an easy thing to be forced to reexamine a way of life and to speculate, in a personal way, on the general injustice.”

The power of Baldwin’s reflection, and the reason it still resonates 62 years later, lies not only in his eloquence, but in his portrayal of three human beings living in the epicenter of historic social change, using details that were still fresh.

Next month, I’m going to talk about Baldwin’s classic “Notes of a Native Son,” a written-from-the-scar kind of story, if you’d like to read ahead.

In the meantime, I’d like to see you start collecting your own observations of our current moment of crisis. So I’ve made you a writing exercise. Hang on to what you come up with – we’ll work with it next month.

Kelly Caldwell

Dean of Faculty