Nutrition Facts

for Hermit Crab Stories

________________________________

Serving Size: One writer, one at a time

Number of Servings per container: Infinite

_________________________________

Ingredients:

One subject the author feels moved to write about;

One desire to experiment or play;

One familiar form of writing† that the author can

borrow for their story;

One imagination.

_________________________________

Calories (spent while writing) — 350 to 500*

Calories (consumed while writing) — 350 to 500**

_________________________________

Percentage (%) daily values

Subject 15%

(These are flash stories, so keep your focus narrow.)

Borrowed Form 75%

(You want your reader to recognize the form immediately, but you should also feel free to play around, take literary license.)

Narrative Arc 100%

(This is still a story with a central character and a clear beginning, middle, and end.)

Voice 50%

(You’ll want your hermit crab to sound like the form you’re borrowing, but don’t abandon your own voice, either. This is still your story.)

Creative Exploration 50%

(Your borrowed shell is firm and imposes some limits; but wearing it enables you to wander further afield, play more, and find a fresh take on something familiar.)

Subject to Shell Matching Ratio ??%

(You might generate a nice frisson of resonance when subject and form share some symmetry. But it’s not necessary. Authors have written about romantic break-ups as auction item catalogue listings and WebMD entries, and I’m borrowing an FDA-regulated label for packaged food for a work on creative writing, so who knows, really?)

___________________________________________________________________________

Key Sources of Inspiration

Flash fiction as obituary 100% ***

Flash essay as resume 100%

Flash fiction as Facebook group rules 100 %

Further reading 100%

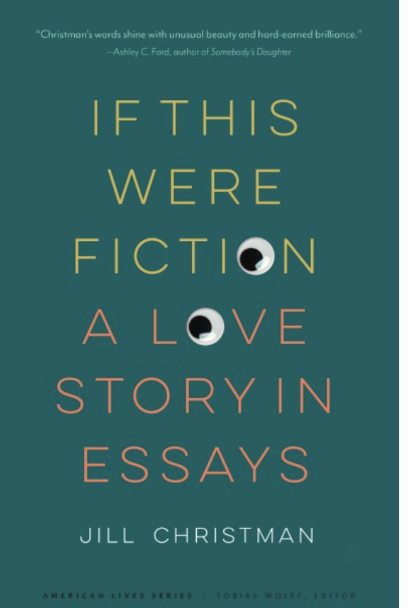

† “A hermit crab essay borrows another form of writing as its structure the way a hermit crab borrows another’s shell. Its subject might be something soft or vulnerable, (like the crab) that seeks the form of something harder or more rigid to encase it. The form must be written but … something less literary and more utilitarian such as a list, recipe, field guide, instruction manual, address book, multiple-choice test, horoscope, Web MD entry…” — Randon Billings Noble

* Will vary based on how angsty a writer you are, and how many times during the writing process you stand up, pace, walk the dog, go for a bike ride, and clean your kitchen.

** See above.

*** If you recognize Deesha Philyaw’s story “Mayretta Kelly Brunson Williams Bryant Jones (1932-2012)” from last June’s Writing Advice, you get a gold star! If you don’t, because you didn’t read it then, consider this your second chance and take the hint.

Kelly Caldwell,

Dean of Faculty