The literary world’s been having a bit of fun lately, pummeling novelist Jonathan Franzen.

In a recent interview, the author of The Corrections revealed that he was unsettled by his feelings of disconnection and bewilderment toward the Milennial generation. He wanted to understand 20-somethings better. So he decided to learn about younger people…by adopting an Iraqi orphan.

The reaction, especially on social media, was pyrotechnic.

People called Franzen everything from “theatrically clueless” (Slate) to a “monster” (assorted anonymous Twitter users). Adoptees were, understandably, offended. “As an adoptee, I’d like to remind everyone we aren’t things you acquire as research material,” wrote literary agent Eric Smith. Even Franzen himself called the idea “insane.”

Eric Smith is right—children aren’t research material.

That said, I think we should all ease up on Jonathan Franzen.

Everyone has ideas that are theatrically clueless, or offensive, or insane. Writers are different. We have those ideas, but we don’t shake them off. We save them, study them. We indulge them. Writers know, seizing on a crazy idea and asking, “What if?” is where the best stories start:

What if you received a postcard that read, “Someone you know has erased you from their memory”? (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind)

What if an autocrat wanted to replace democracy in the United States with a dictatorship; how would he/she accomplish it? (The Handmaid’s Tale)

What if a novelist adopted an orphaned refugee to better understand young people?

OK, that last one hasn’t been written—yet. But you can imagine it. Admit it: You’re already casting the movie.

Not only should we let up on Franzen because writers need to indulge their outlandish ideas, but also because we often go to crazy lengths for research. Writers research the way athletes train and musicians rehearse. It’s how we make our stories real and true.

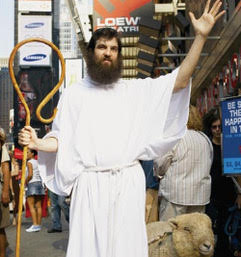

Writers have watched autopsies, ridden mounted patrol with police officers, and squeezed into cockpits with pilots. Nonfiction author A.J. Jacobs tried to follow every rule laid out in the Bible (The Year of Living Biblically). Novelist Philipp Meyer shot a buffalo and drank its blood (The Son).

If you’re writing a drama set at an Oklahoma funeral where the tension comes from some spectacular but not-exactly-unheard-of dysfunctional family dynamics (August: Osage County), I’m not saying chuck it, drink some buffalo blood, and then go skydiving.

I’m saying when that outrageous “What if?” about the nephew character floats into your mind, don’t dismiss it. Indulge it. Research the hell out of it. See where both idea and research lead.

The place where they intersect, chances are, that’s where your best story awaits. You wouldn’t want to miss it, just to avoid seeming theatrically clueless.

Cheers,

Kelly Caldwell

Dean of Faculty