Recently, while out with a writer friend, I asked what she’d been up to lately. “Today I finally found the lede for the story I’m working on,” she said. She paused a moment. “Isn’t that the best feeling? When you find your lede?”

For those of you not familiar with “lede,” it’s a word some nonfiction writers use for a story’s beginning. And yes, when you find your story’s beginning, the true, right beginning, it’s an exhilarating moment, indeed.

In any kind of creative writing, those first few lines can be the most crucial. After all, fail to draw your reader into the story and all the work you’ve done on the rest of the story will be for nothing. It’s a lot of pressure, and one reason why finding your lede can be so hard.

To help writers out, the editors over at Penguin Random House have published a list of things they look for on the first page of a manuscript. It’s a good list, and helpful. I recommend reading it.

But it’s also a little frustrating. Because their first item is: A powerful opener.

“The power of the opening cannot be overstated,” they write. And, that’s true. A “powerful” opening is what editors, producers, writers, teachers, critics, agents, and my dad all say they look for in any story.

But what, exactly, makes an opening powerful?

Life-and-death scenes almost always qualify, like this opening from Outside magazine: “Michael Utley does not remember much about his death.”

For high-stakes, it’s hard to beat starting with a near-death experience.

The same goes for passion: “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta…” (Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov).

Or confrontation: “What you looking at me for?” (I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, Maya Angelou)

So, must every opening feature cars streaking toward cliffs, or gamblers betting the family home on red, to achieve power?

No. A story doesn’t have to be a tabloid-ready drama of death, destruction, and debauchery to be powerful. Neither, then, does its beginning.

Take the first sentence of Wallace Stegner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Angle of Repose: “Now I believe they will leave me alone.”

It’s quiet, yet to me just as gripping as the life-and-death beginnings. The “now” implies that whoever “they” are, they hadn’t left the narrator alone before. But he’s done something to ensure that they will. I wonder what that could be. And I wonder why he’d want them to.

Stegner’s opening evokes desire, and loneliness. It cuts to the emotional core of his story. He plunges straight into its heart.

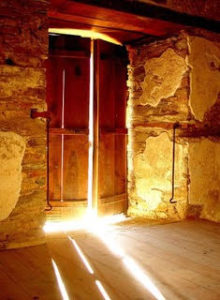

That, ultimately, is the source from which truly powerful openings flow: the human heart.

Kelly Caldwell

Dean of Faculty